This was not a nice feeling. I started to work out possible plans of action. I could turn back, which would mean at least half an hour flying through known icy conditions. I could descend and hope to break out of the clouds before hitting the ground. I could just continue and hope for the best. After all, I had been flying without problems through the ice for half an hour now. Only problem was, I didn’t know how long the icing conditions would last. Or, I could descend and divert to Taloyoak, which should be a few miles west of me, about 15 minutes away.

I cursed the weather man (freezing level around 10 000 ft, right!) and dismissed the turning back option, since that was the only option that guaranteed me another 30 minutes of ice on the wing. I heard on the Taloyoak frequency that the weather was deteriorating there quite quickly, and they had a ceiling around 900 ft at the time. Taloyoak had an elevation of 92 feet, but there were hills with elevations up to 600 ft around, and some obstacles that were even higher. This made me dismiss the “divert to Taloyoak” option. I was going to try to descend down t o 3000 ft maximum, and see if I would break out of the clouds. Going lower would be useless, since the terrain would start to rise in another hour. A quick descend later, I broke out of the clouds at 4000 ft, only to see another layer below me, almost reaching the ground and another wall of clouds a few kilometers before me. This wasn’t going to work out, so I started my chase for the sun again. Climbing back towards the sun, and checking the wing every 10 seconds, I reached my cruising level of 7000 ft again without collecting any more ice. Ten minutes later I was clear of clouds. Half an hour later all the ice was melted and I continued as happily as before.

An hour later, I had to enter another cloud, with again the same icing effect. This time, I knew what to expect, and half an hour later, the ice started to melt again. The last part of the flight was flown in the nice sunny weather I’d gotten used to. The scenery started to change again. Almost no vegetation, just rocks and water. Lots of water. I saw the first ice of the trip, and some isolated remains of what was one giant area of ice a few weeks earlier.

After 7 hours of flying, I saw the first glimpse of the destination. I radioed the airport, and asked them to inform Aziz of my arrival. The radio was very difficult to read, which made me unsure if my message got through. In the middle of the rocks and water, a shore line appeared. In this shore line, a little bay was forming. Little houses popped up, and 7 kilometers to the west, another group of buildings became visible. The gravel runway was a bit difficult to see, so I made a nice by the book visual approach. Circling overhead, joining left hand downwind (first time this was over an icy sea), trying to keep a visual on the runway (which is not as easy as it looks when everything you see is gravel anywhere). The clouds were at 2000 ft, very dark. I made a smooth landing and taxied to the apron. The ‘tower’ told me I could park anywhere I wanted. Parking anywhere you want in the North means that the parking spot you first select will always be a wrong space, which will mean you have to move somewhere else, exactly where they tell you to, which included a complete useless taxi at slow speed and high power through a gravel apron. Trying not to damage the plane, I reached my final taxi stop. The tower closed my flight plan and I jumped out of the plane, to be immediately greeted by Aziz. The local business man running half of Resolute Bay, who sold me the fuel and offered me accommodations.

I didn’t want to keep him off his work for too long, so I rushed through the plane to collect all my gear. I wouldn’t need my tent to sleep, as he promised he would take care of me. No tie downs were necessary either, as he told me the airport guys would call him if the wind would pick up above 15 kts. All the stuff was packed in his car. It was then I recognized the car: it was a bloody Mercedes! A nearly new silver Mercedes, driving around at 70°N, in a dusty gravel environment.

After a stop at his car shop, where Aziz helped some people fixing a truck, I arrived at his hotel. I updated the friendly people on the AvCanada forum and informed a local pilot I was staying at Aziz’s hotel. I had a lovely dinner made by Randy, Aziz’s cook. I would see Randy a lot the next week, but more about that later.

I made a little stroll through the village and the bay. Resolute Bay. A little later the pilot dropped by for a visit and gave me some more information about flying here. The house keeping lady of the hotel was also a social match maker, and informed a reporter that there was a crazy guy planning to fly to the North Pole in a small airplane. She made a quick interview with me, to feature in her ‘Arctic Explorers’ story. The house keeping lady had the time of her life setting up the interview room with all kinds of props left behind by other travelers. This included a canoe, a dead muskox and some hiking gear. Jane was actually there to jump on an Ice Breaker on its way to Cambridge Bay, telling a story about the North Western Passage, an area still a bit in dispute to whom it actually belongs.

Feeling like a movie star after my interview, I went to bed. I was really high up in the Arctic by now. And I would go higher.

To be continued ...

Disclaimer: This is a work of fiction, loosely based on a true story. This is not an official report in any way. All rights reserved.

----------

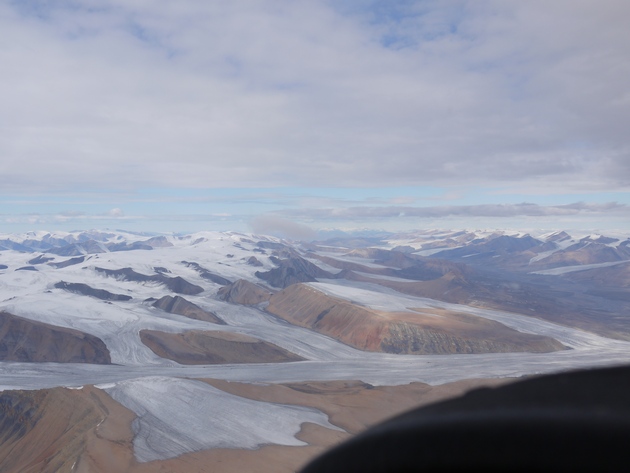

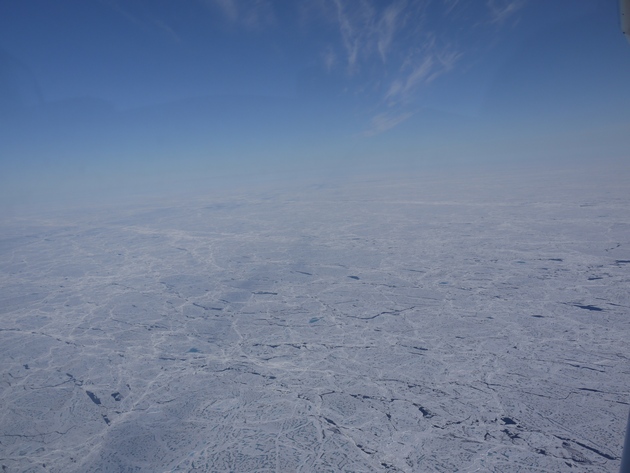

On my way to Resolute Bay

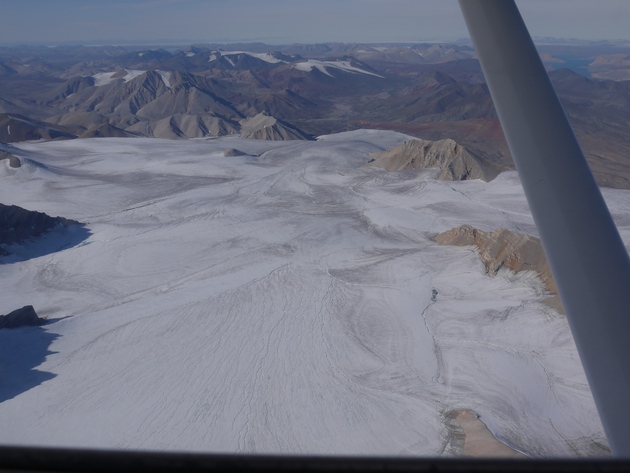

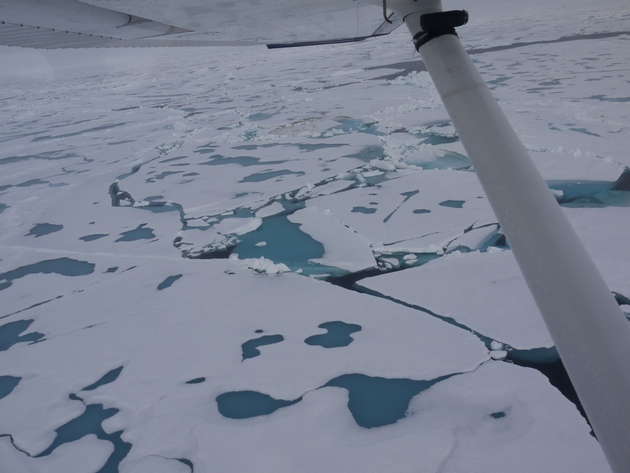

The first ice in the water

The first ice on the wing

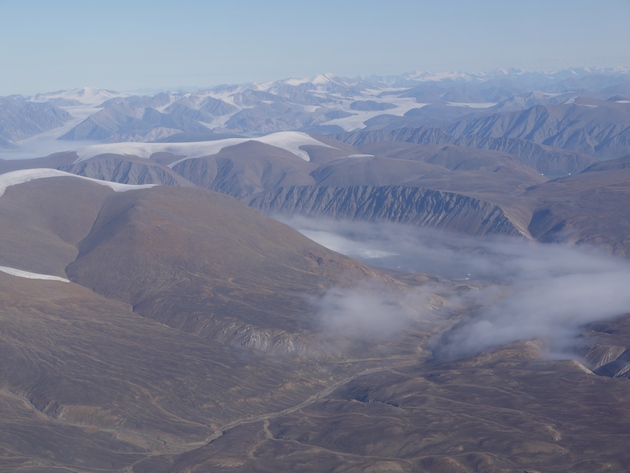

Low clouds and a beautiful scenery

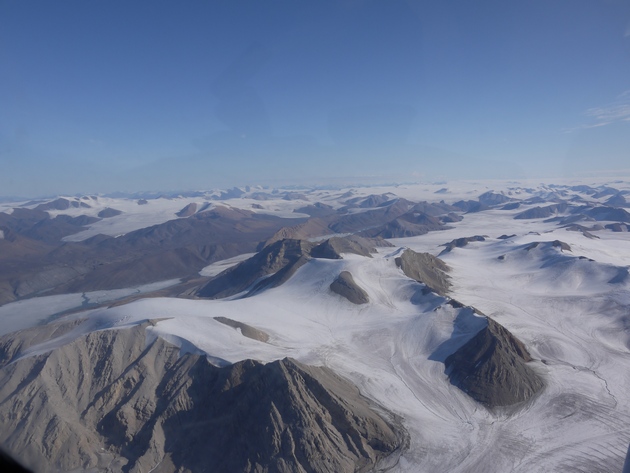

Little rocky hills

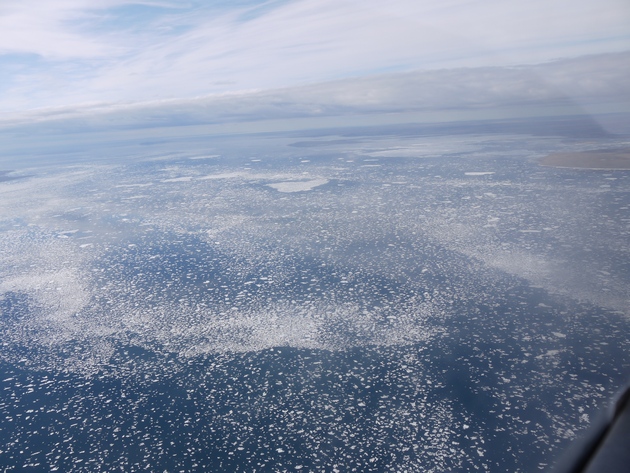

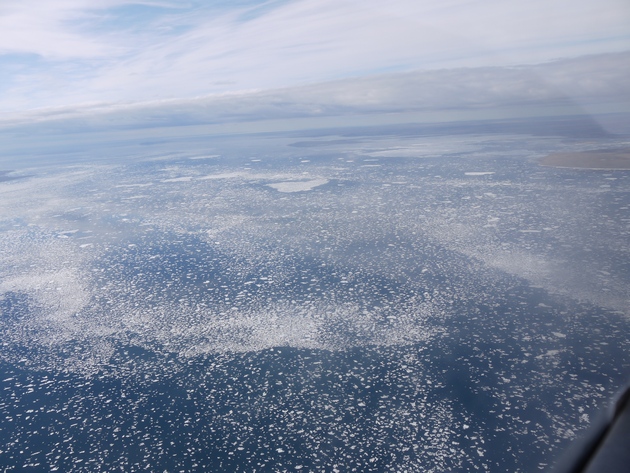

Crossing the final water

Final in Resolute Bay airport

Resolute Bay, the Bay itself

I cursed the weather man (freezing level around 10 000 ft, right!) and dismissed the turning back option, since that was the only option that guaranteed me another 30 minutes of ice on the wing. I heard on the Taloyoak frequency that the weather was deteriorating there quite quickly, and they had a ceiling around 900 ft at the time. Taloyoak had an elevation of 92 feet, but there were hills with elevations up to 600 ft around, and some obstacles that were even higher. This made me dismiss the “divert to Taloyoak” option. I was going to try to descend down t o 3000 ft maximum, and see if I would break out of the clouds. Going lower would be useless, since the terrain would start to rise in another hour. A quick descend later, I broke out of the clouds at 4000 ft, only to see another layer below me, almost reaching the ground and another wall of clouds a few kilometers before me. This wasn’t going to work out, so I started my chase for the sun again. Climbing back towards the sun, and checking the wing every 10 seconds, I reached my cruising level of 7000 ft again without collecting any more ice. Ten minutes later I was clear of clouds. Half an hour later all the ice was melted and I continued as happily as before.

An hour later, I had to enter another cloud, with again the same icing effect. This time, I knew what to expect, and half an hour later, the ice started to melt again. The last part of the flight was flown in the nice sunny weather I’d gotten used to. The scenery started to change again. Almost no vegetation, just rocks and water. Lots of water. I saw the first ice of the trip, and some isolated remains of what was one giant area of ice a few weeks earlier.

After 7 hours of flying, I saw the first glimpse of the destination. I radioed the airport, and asked them to inform Aziz of my arrival. The radio was very difficult to read, which made me unsure if my message got through. In the middle of the rocks and water, a shore line appeared. In this shore line, a little bay was forming. Little houses popped up, and 7 kilometers to the west, another group of buildings became visible. The gravel runway was a bit difficult to see, so I made a nice by the book visual approach. Circling overhead, joining left hand downwind (first time this was over an icy sea), trying to keep a visual on the runway (which is not as easy as it looks when everything you see is gravel anywhere). The clouds were at 2000 ft, very dark. I made a smooth landing and taxied to the apron. The ‘tower’ told me I could park anywhere I wanted. Parking anywhere you want in the North means that the parking spot you first select will always be a wrong space, which will mean you have to move somewhere else, exactly where they tell you to, which included a complete useless taxi at slow speed and high power through a gravel apron. Trying not to damage the plane, I reached my final taxi stop. The tower closed my flight plan and I jumped out of the plane, to be immediately greeted by Aziz. The local business man running half of Resolute Bay, who sold me the fuel and offered me accommodations.

I didn’t want to keep him off his work for too long, so I rushed through the plane to collect all my gear. I wouldn’t need my tent to sleep, as he promised he would take care of me. No tie downs were necessary either, as he told me the airport guys would call him if the wind would pick up above 15 kts. All the stuff was packed in his car. It was then I recognized the car: it was a bloody Mercedes! A nearly new silver Mercedes, driving around at 70°N, in a dusty gravel environment.

After a stop at his car shop, where Aziz helped some people fixing a truck, I arrived at his hotel. I updated the friendly people on the AvCanada forum and informed a local pilot I was staying at Aziz’s hotel. I had a lovely dinner made by Randy, Aziz’s cook. I would see Randy a lot the next week, but more about that later.

I made a little stroll through the village and the bay. Resolute Bay. A little later the pilot dropped by for a visit and gave me some more information about flying here. The house keeping lady of the hotel was also a social match maker, and informed a reporter that there was a crazy guy planning to fly to the North Pole in a small airplane. She made a quick interview with me, to feature in her ‘Arctic Explorers’ story. The house keeping lady had the time of her life setting up the interview room with all kinds of props left behind by other travelers. This included a canoe, a dead muskox and some hiking gear. Jane was actually there to jump on an Ice Breaker on its way to Cambridge Bay, telling a story about the North Western Passage, an area still a bit in dispute to whom it actually belongs.

Feeling like a movie star after my interview, I went to bed. I was really high up in the Arctic by now. And I would go higher.

To be continued ...

Disclaimer: This is a work of fiction, loosely based on a true story. This is not an official report in any way. All rights reserved.

----------

On my way to Resolute Bay

The first ice in the water

The first ice on the wing

Low clouds and a beautiful scenery

Little rocky hills

Crossing the final water

Final in Resolute Bay airport

Resolute Bay, the Bay itself